Dec 10, 2025

Beyond the Hype: The Industrial Reality of 3D Printed Footwear

High-fashion runways and athletic giants have proven that 3D printed footwear is a cultural force, but the core challenge remains: how do you transition from a single prototype to manufacturing thousands of pairs reliably and cost-effectively? At DHR Engineering, we put our automated farm to the test with a continuous 48-hour production cycle. And we learned something valuable about the automation pillars required to turn additive manufacturing into a scalable industrial reality.

3D Printing

Footwear

Manufacturing

This article explores:

Overview

The excitement surrounding 3D printed footwear is palpable. With their futuristic lattice structures and avant-garde silhouettes, these shoes are no longer a niche concept but a cultural and commercial force. High-fashion houses like Louis Vuitton and Dior have debuted printed designs on the runway, while athletic giants such as Adidas have brought millions of pairs to the mass market.

But for manufacturers, consumer hype obscures the core industrial challenge: How do you transition from producing a novel prototype to manufacturing thousands of pairs reliably, cost-effectively, and at scale?

At DHR Engineering, we don’t just speculate on the answer; we engineer it.

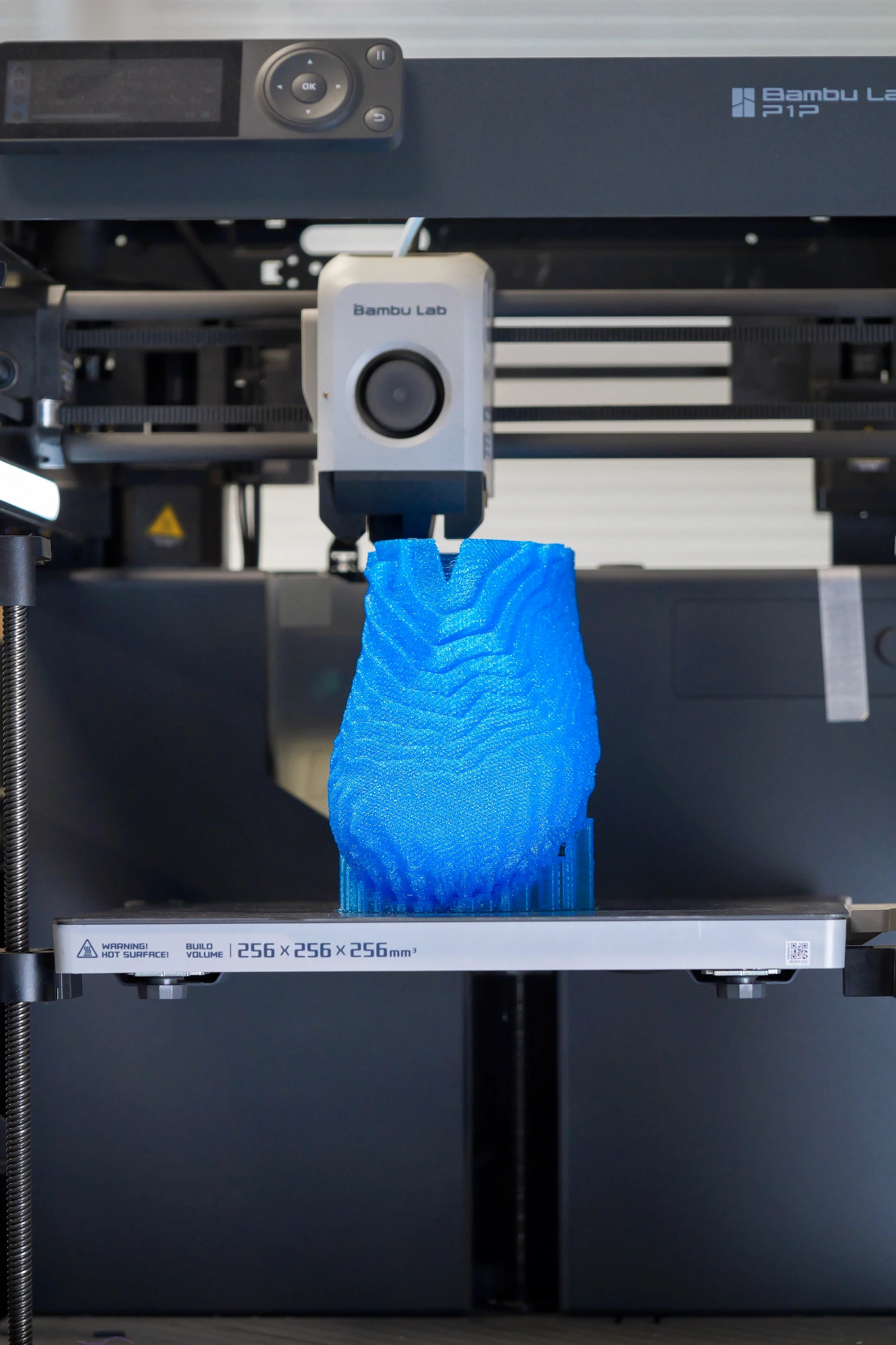

We recently put our own automated farm to the test, running a continuous 48-hour print cycle. Utilizing our in-house automation handling 44 FDM machines, we proved that making one shoe is a design achievement, but making thousands is an achievement in process engineering.

Here is what we learned about the economics, the technology, and the automation required to make it work.

Old vs New Ways

The Manufacturing Revolution: Why Footwear is Ripe for Disruption

To understand why we ran this test, you have to look at the limitations of the traditional footwear model. For over a century, the industry has relied on a mold-based, labor-intensive workflow optimized for low-mix, high-volume production in distant factories.

The shift to Additive Manufacturing (AM) isn't just about cool shapes; it’s about breaking the shackles of legacy manufacturing, which has certain limitations:

Tooling: Traditional manufacturing relies on expensive molds. If you want to change a design, you have to cut new metal. In an additive workflow, the "mold" is just a digital file. We can change the design instantly without spending a dime on tooling.

Supply Chain: The old model is centralized. You make millions of units in a massive factory in Asia and ship them across the ocean. The new model is decentralized. You can print just-in-time, closer to where the customer actually lives.

Waste: Cutting patterns out of fabric or foam creates huge amounts of scrap. 3D printing is additive and only uses the material needed for the shoe.

This shift is compelled by powerful market drivers that are reshaping supply chains:

Mass Customization: Modern consumers demand personalization. Ten years ago, 3D scanning was expensive; today, the LiDAR scanner in your iPhone has democratized data capture. Consumers can now send a precise biomechanical map of their foot directly to a manufacturer, making custom fits a reality. Companies like Zellerfeld exemplify this shift by offering custom-fitted footwear.

Generative AI: Algorithms optimize complex lattice structures for specific performance metrics. This shifts complexity from physical assembly to scalable software, allowing thousands of design iterations with zero tooling costs. A leading example is the Adidas 4DFWD running shoe, which uses a 3D-printed, anisotropic lattice midsole to specifically redirect vertical impact forces into forward motion.

Local Production: The fragility of global supply chains is now a critical business risk. Localized, on-demand production mitigates exposure to shipping delays and geopolitical tensions. This has sparked reshoring initiatives, like California-based startup Koobz, which recently raised $7.2 million to build domestic manufacturing capacity.

Sustainability: AM offers verifiable environmental benefits, potentially reducing emissions by 48% and water consumption by 99%. By utilizing "mono-material" designs, we can eliminate the adhesives that make standard shoes impossible to recycle, paving the way for a truly circular economy.

While these technologies create a revolutionary shoe, it is industrial automation that allows that shoe to be produced at a revolutionary scale and a low price required for broad market penetration.

The napkin math

The Business Case: Automation, Economics, and Scale

The biggest barrier to adopting additive manufacturing (AM) for footwear has always been cost. For a long time, it was simply cheaper to manufacture in Asia. But the math is changing.

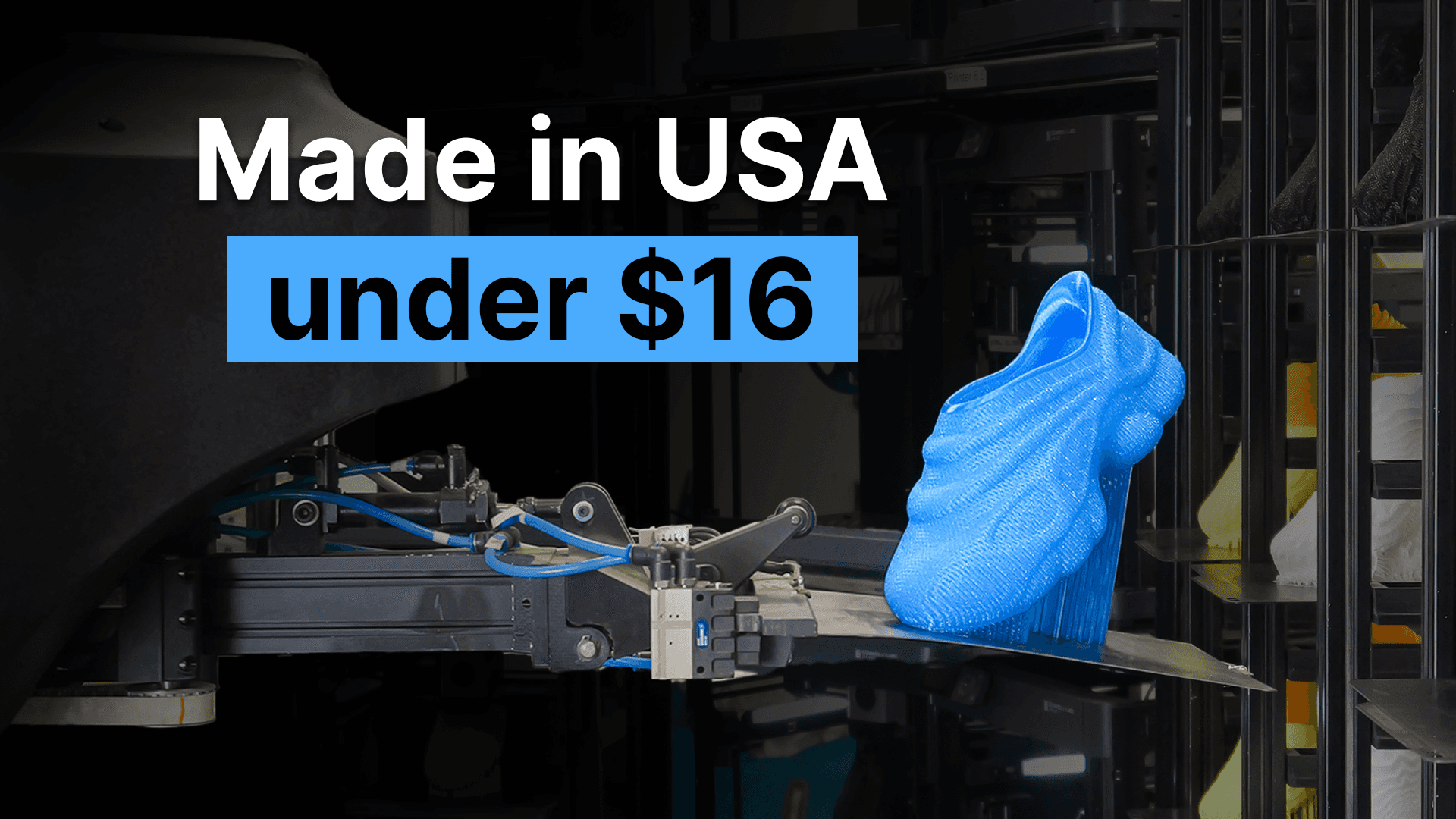

In our recent automated run, we analyzed the real production cost of 3D printed footwear by looking at material consumption, electricity use, machine depreciation, and labor (one operator for 1 hour per day). The calculated cost for producing a finished pair of sneakers in an automated print farm with 300 machines, localized in California, USA, came out to approximately $15.42 per pair.

That number is closer, if not cheaper, than traditional overseas footwear sourcing than many assume. Low-end sneakers sourced from factories in China may start around $6.50–$9 per pair, while better-quality production, comparable to an Adidas Samba, typically lands closer to $25 ex-works. For new designs, tooling costs add up quickly. Injection-molded footwear requires a separate mold per size, typically around $1,400 each. Once shipping, tariffs (currently around 37%), customs, inventory risk, branding and customization, packaging, and large MOQs are accounted for, the landed cost increases significantly.

The Automation Ecosystem

Scaling to a million pairs requires a system where machines operate autonomously. At DHR, we rely on three pillars to achieve the efficiency required to hit that $15.42 price point:

Robotic Tending: Humans should not load printers. Our custom-built robot handles the entire machine fleet, handling bed loading and unloading without breaks, ensuring continuous 24/7 throughput and significantly decreasing labor costs.

Centralized Control: A "software brain" manages the farm, scheduling jobs, monitoring status, and automatically re-routing tasks if a print fails. This removes the need for constant human oversight.

Automated Post-Processing: Taking the shoe off the printer is only step one. Washing, depowdering, and surface finishing (if using SLA or SLS technology for components) must be automated to prevent the factory from becoming a bottlenecked prototyping lab.

The Real ROI: Quantifying the Value of an Automated Workflow

When this ecosystem runs correctly, the ROI extends far beyond simple labor arbitrage:

Operational Savings: Automation achieves 95%+ machine uptime and enables a single operator to manage the entire print farm for 1 hour per day, which drastically reduces machine-tending labor.

Speed & Flexibility: Design updates are software-based, shrinking the "design-to-shelf" cycle from months to days without re-tooling costs.

Inventory Elimination: On-demand production removes the risk of unsold stock and the capital trap of Minimum Order Quantities (MOQs).

Unlocking New Revenue Through Mass Customization: Automation makes personalization economically viable at industrial scale. This capability directly addresses the demands of a market projected to reach USD 5.38 billion by 2030.

Conclusion

Lessons from the Factory Floor: The Path Forward

The path to scaled additive manufacturing is clearer than ever, but it is defined by the lessons learned from early industrial experiments. The technology was never the barrier; the strategy was.

The most crucial cautionary tale is that of the Adidas Speedfactory. Its failure was not a failure of automation, but a misapplication of it. They attempted to apply complex robotics to legacy processes (cutting, stitching, bonding). The industry lesson is now clear: True efficiency comes from redesigning the product for automation, not just automating old workflows.

Successful emerging models are embracing this principle:

The Component Focus: Adidas and Carbon succeeded by focusing automation on a single, high-value component (the 4D midsole), perfecting the process for one part before tackling the whole shoe.

The Platform Model: Innovators like Zellerfeld are building open platforms that allow independent designers to bring creations to market without upfront capital, effectively democratizing footwear design and production.

The Full-Shoe Vision: By designing "mono-material" products that require no assembly, we unlock the potential for a circular supply chain where old shoes can be ground down and reprinted into new ones.

At DHR Engineering, we see this evolution firsthand. 3D printing provides the unprecedented design freedom to create the footwear of the future, but only robust, intelligent industrial automation can deliver that promise at scale.

If you're facing throughput challenges or planning a fully automated production workflow, let’s talk. We build the automation that makes the future of manufacturing a reality.